decision <- function(draws_a, draws_b){

diff <- draws_b - draws_a

loss_a <- mean(pmax(diff, 0))

loss_b <- mean(pmax(-diff, 0))

if(loss_a < loss_b){

winner <- "A"

} else {

winner <- "B"

}

list(winner=winner, loss_a=loss_a, loss_b=loss_b)

}Introduction

Bayesian decision making with loss functions was a very popular with stakeholders and data scientists when I was working in AB testing. In short, eschew p values instead ask “If I made this decision, and I was wrong, what do I stand to lose?” and then make the decision which minimizes your expected loss. In my opinion, and from what I’ve heard from others, this is an attractive method because it places the thing we care most about (usually revenue, or improvement to the metric) at the heart of the decision.

But while Bayes is nice for decision making, I would always get the same question from stakeholders: “How long do we run the experiment”? As a frequentist, you can answer this by appealing to statistical power, but Bayes has at least more options. Kruschke 1 argues for using posterior precision as a stopping criterion, others (e.g. David Robinson2) have mentioned setting some threshold for expected loss. These seem to be the most popular from what I’ve read, and I think both of these make a lot of sense – especially the stopping criterion based on precision. But that doesn’t really answer my question. I want to answer “how long do we have to run the experiment”, which should be answered in a unit of time and not “until your precision is \(x\)”. Answering in this way just results in another question, such as “how much precision do I need”. Additionally, these approaches have no time element – the experiment could go on for much longer than we might be willing to accept, and we may still not reach our stopping criterion. What do we do in those cases, and how do we understand the trade offs? How do I prevent stakeholders from using the stopping without the stopping criterion as precedence for running under powered experiments? I don’t have answers to those questions.

When I asked about this on twitter, a few people mentioned The Expected Value of Sample Information (EVSI) which I think is closer to what I want. In short, the EVSI helps us understand the change in expected loss the decision maker could obtain from getting access to an additional sample before making a decision. This is closer to what I want, because now I could say to a stakeholder “Don’t/Stop now, there is a \(p\%\) chance the results would change in a week”. It may not be a direct answer for how long, but its closer. Additionally, Carl Vogel (then of Babylist) seemed to be using this approach, as explained in his posit::conf 2023 talk3, so it seems like SOMEONE is doing this already and I’m not just crazy.

I think the EVSI approach is good, but I have lingering questions, mostly about calibration. So in this post, I want to run a few simulations to see how well calibrated this procedure can be in the case where we run an experiment with two variants and a binomial outcome. I’ll set up some math as a refresher, then we’ll dive into the simulations.

Refresher on Decision Making

Suppose I launch a test with two variants. I’m interested in estimating each variant’s mean outcome, \(\theta\) (which for all intents and purposes could a conversion rate for some process). I collect some data, \(y\), and I get posterior distributions for each \(\theta\), \(p(\theta \mid y)\). I need to make a decision about which variant to launch, and I want to do that based on their mean outcomes, but I don’t know the mean outcomes perfectly. One way to make the decision is through minimizing expected loss. Let \(\mathcal{L}(\theta_A, \theta_B, x)\) be the loss I would incur were I to launch variant \(x\) (e.g. A/B) when in truth \(\neg x\) (e.g. B/A) was the superior variant. The expected loss for shipping \(x\) is provided by the following integral

\[ E[\mathcal{L}](x) = \int_{\theta_A} \int_{\theta_{B}} \mathcal{L}(\theta_A, \theta_B, x) p(\theta_A, \theta_{B} \mid y_B, y_B) \, d\theta_A \, d\theta_B \>, \]

where \(p\) is the joint posterior distribution of \(\theta_A, \theta_B\). The decision, \(D\), we should make is to launch the variant which results in smallest expected loss

\[ D = \underset{{x \in \{A, B\}}}{\operatorname{arg min}} \left\{ E[\mathcal{L}](x) \right\} \>. \]

For more on this sort of evaluation for AB testing, see this report by Chris Stucchio. In what follows, I’m going to use the following loss function

\[ \mathcal{L}(\theta_A, \theta_b, x) = \begin{cases} & \max(\theta_B-\theta_A, 0) \>, & x=A \\\\ & \max(\theta_A-\theta_B, 0) \>, & x=B\end{cases} \> \]

I interpret this loss function to be the improvement to the mean outcome we would has missed out on, had we shipped the wrong variant. As an example, if we ship A but B is truly better, then we lose out on a total of \(\theta_B - \theta_A\). If we ship A and A is truly the superior variant, then we lose out on 0 improvement to the metric (because we chose right). Note that this works for revenue too! This decision can be written succinctly in code using draws from the posterior as follows

Quick Primer on EVSI

The expected loss from the optimal decision given the data \(y_A, y_B\) would be

\[\begin{align*} E[\mathcal{L}](D) &= \underset{{x \in \{A, B\}}}{\operatorname{min}} \left\{ E[\mathcal{L}](x) \right\} \\ &= \underset{{x \in \{A, B\}}}{\operatorname{min}} \int_{\theta_A} \int_{\theta_{B}} \mathcal{L}(\theta_A, \theta_B, x) p(\theta_A, \theta_{B} \mid y_A, y_B) \, d\theta_B \, d\theta_A \end{align*} \]

Suppose I had the opportunity to gain additional samples. Were I to observe \(\tilde{y}_A, \tilde{y}_B\), the expected loss would be

\[ E[\mathcal{L}](\tilde{D})= \underset{{x \in \{A, B\}}}{\operatorname{min}} \int_{\theta_A} \int_{\theta_{B}} \mathcal{L}(\theta_A, \theta_B, x) p(\theta_A, \theta_{B} \mid y_A + \tilde{y}_A, y_B + \tilde{y}_B) \, d\theta_B \, d\theta_A \] where \(\tilde{D}\) is the optimal decision from the new data. Of course, we can’t say what this optimal decision would be since we don’t know the new data. But, having a model for these data, we could sample from that model and integrate over the uncertainty for \(\tilde{y}_A, \tilde{y}_B\). That means we would compute

\[ E[\mathcal{L}](\tilde{D})= \int_{\theta_a} \int_{\theta_b}\underset{{x \in \{A, B\}}}{\operatorname{min}} \int_{\tilde{\theta}_A} \int_{\tilde{\theta}_{B}} \mathcal{L}(\tilde{\theta}_A, \tilde{\theta}_B, x) p(\tilde{\theta}_A, \tilde{\theta}_{B} \mid y_A + \tilde{y}_A, y_B + \tilde{y}_B) p(\tilde{y}_A, \tilde{y}_B \mid \theta_A, \theta_B ) p(\theta_A, \theta_B \mid y_A, y_B) \, d\tilde{\theta}_B \, d\tilde{\theta}_A \, d\theta_B \, d\theta_A \]

Now, this looks like a right hairy integral. However, its straightforward to understand. Consider the following process:

- Use the posterior predictive (\(p(\tilde{y}_A, \tilde{y}_B \mid \theta_A, \theta_B ) p(\theta_A, \theta_B \mid y_A, y_B)\)) to sample data you would have seen were you to continue the experiment.

- Act as if that data was the true data and condition your model on it to obtain your future updated posterior (\(p(\tilde{\theta}_A, \tilde{\theta}_{B} \mid y_A + \tilde{y}_A, y_B + \tilde{y}_B)\))

- Compute the optimal loss for each decision having seen that data

- Determine what decision you would make had that been the data you would have seen.

- Repeat for as many draws from the posterior predictive as you like, and average over samples.

The EVSI should then be

\[EVSI = E[\mathcal{L}](D) - E[\mathcal{L}](\tilde{D}) \]

which can be understood as the expected reduction in expected loss were you to continue sampling.

EVSI, Changing One’s Mind, and Calibration

While EVSI can be used to determine if one should continue to sample based on costs and expected benefits, I am interested in a slightly different question. Ostensibly, EVSI can be used to justify continued sampling in the event one variant looks like a winner because, as Carl Vogel says, “[each future] posterior may not change my mind at all based on what I was going to do under the prior. They may change my mind a lot based on what I was going to do under the prior”. This leads me to ask about calibration for changing my mind. If this procedure tells me there is a \(p\%\) I change my mind about which variant to ship, do I actually change my mind \(p\%\) of the time?

The answer is “Yea, kind of”! To see this, let’s do some simulation. I’ll simulate some data from a two variant AB test with a binary outcome. Then, I will compute the EVSI and determine if more data might change my mind as to what variant I might ship. Then, I’ll simulate additional data from the truth to see if my mind would have changed.

From there we can determine the calibration by looking at the proportion of simulations in which my mind actually changed, versus the proportion of simulations in which the EVSI computation forecasted I would have changed my mind. The code is in the cell below if you want to look at how I do this.

Here is a high level overview of the simulation:

- The true probability in group A is 10%.

- The true probability in group B is 10.3% (a 3% lift).

- We get 20, 000 subjects in the experiment per week, which is 10, 000 in each group per week.

- We run the experiment for a single week and ask “If I ran for one more week, might I change my mind about what I ship”?

- We use a beta binomial model for the analysis, and we have an effective prior sample size of 1000 (our priors are \(\alpha = 100\) and \(\beta=900\)).

I realize there are a lot of hyperparameters we could tune here: More/fewer samples, higher/lower lift, day of week effects, etc etc. I’m going to keep it very simple for now and let you experiment as you see fit. This also means I can’t make sweeping statements about how well this performs or not.

Code

library(tidyverse)

true_probability_a <- 0.1

true_lift <- 1.03

true_probability_b <- true_probability_a * true_lift

N <- 10000

nsims <- 1000

ALPHA <- 100

BETA <- 900

future::plan(future::multisession, workers=10)

results <- furrr::future_map_dfr(1:nsims, ~{

# Run the experiment and observe outcomes

ya <- rbinom(1, N, true_probability_a)

yb <- rbinom(1, N, true_probability_b)

# Compute the posterior

posterior_a <- rbeta(1000, ALPHA + ya, BETA + N - ya)

posterior_b <- rbeta(1000, ALPHA + yb, BETA + N - yb)

# What decision would we make RIGHT NOW if we had to?

out_now <- decision(posterior_a, posterior_b)

current_decision <- out_now$winner

current_loss_a <- out_now$loss_a

current_loss_b <- out_now$loss_b

# What might we see in the future, conditioned on what we know now?

forecasted_out <- map(1:nsims, ~{

theta_a <- sample(posterior_a, size=1)

theta_b <- sample(posterior_b, size=1)

future_y_a <- rbinom(1, N, theta_a)

future_y_b <- rbinom(1, N, theta_b)

future_posterior_a <- rbeta(1000, ALPHA + ya + future_y_a, BETA + 2*N - ya - future_y_a)

future_posterior_b <- rbeta(1000, ALPHA + yb + future_y_b, BETA + 2*N - yb - future_y_b)

decision(future_posterior_a, future_posterior_b)

})

# Laplace smoothing to make sure there is always a non-zero chance of something happening.

forecasted_winners<- c("A", "A", "B", "B", map_chr(forecasted_out, 'winner'))

forecasted_loss_a <- map_dbl(forecasted_out, 'loss_a')

forecasted_loss_b <- map_dbl(forecasted_out, 'loss_b')

prob_mind_change <- mean(forecasted_winners != current_decision)

# Now, run the experiment into the future to see if we changed our minds

ya <- ya + rbinom(1, N, true_probability_a)

yb <- yb + rbinom(1, N, true_probability_b)

# Compute the posterior

posterior_a <- rbeta(1000, ALPHA + ya, BETA + 2*N - ya)

posterior_b <- rbeta(1000, ALPHA + yb, BETA + 2*N - yb)

# What decision would we make RIGHT NOW if we had to?

future_decision <- decision(posterior_a, posterior_b)

mind_changed <- as.numeric(future_decision$winner != current_decision)

tibble(current_winner = current_decision,

future_winner = future_decision$winner,

mind_changed,

prob_mind_change,

forecasted_evsi_a = current_loss_a-mean(forecasted_loss_a),

forecasted_evsi_b = current_loss_b-mean(forecasted_loss_b),

true_evsi_a = current_loss_a - future_decision$loss_a,

true_evsi_b = current_loss_b - future_decision$loss_b)

},

.progress = T,

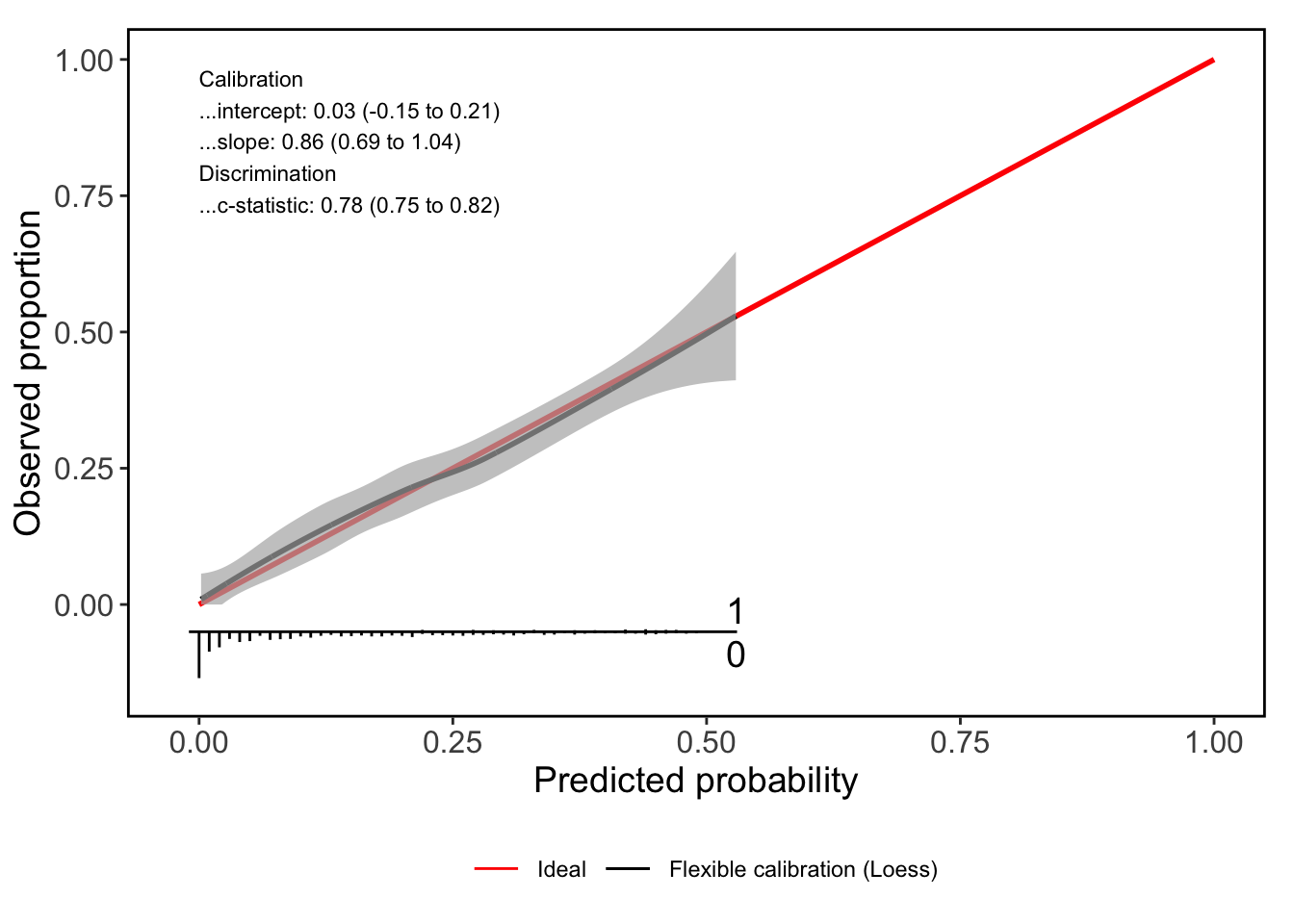

.options = furrr::furrr_options(seed =T))Calibration results are shown below. Its…not bad, right? I suppose if this calibration really irked you then you could run this simulation assuming the true lift was \(z\%\), and recalibrate the estimates using whatever procedure you like!

Code

out <- with(results, CalibrationCurves::valProbggplot(prob_mind_change, mind_changed))

out$ggPlot

Conclusions

I really like EVSI, and generally this whole procedure for thinking about if we should continue to collect data or not. The results from this tiny little simulation are not intended to be generalizable, and they very likely depend on things like the prior, how much additional data you would collect, and the priors for the model. However, I’ve chosen these parameters to roughly reflect real world scenarios I came across working in AB testing, so this is really encouraging to me!

So how would I answer a stakeholder who wanted to know how long to run the test if they wanted to use a Bayesian method? Generally I might advise a minimum run length of 1 week (so we can integrate over day of week effects). Then, its all sequential from there! Use this procedure to determine the probability you change your mind, and how much the additional sample might change your mind in terms of revenue/improvement/whatever your criterion is. There may come a time at which no more data would change your mind (at least according to the data you’ve seen so far) and at that point the inference problem is kind of irrelevant.

Generally, there are no “right” procedures when it comes to decision making – only trade offs. I particularly like this approach because its good at triaging risk, which is what I think data science should be.